The Vanner Gallery, Salisbury, September 17th - December 24th 2021

Salisbury has had a tough few years, but it’s kicking against the trend - three years after those poisonings, amidst the gloom of post-Brexit anxiety and a year and a half of hiding from the pandemic, a new contemporary art gallery is opening; a bold mark of intent and faith in the future of the city that is enormously optimistic and refreshing. Its location couldn’t be better, overlooking the medieval High Street gate into the famed cathedral close. When the tourists come back (and some have been spotted already) they will, at the very least, walk the quarter mile from that ancient stand of beautiful buildings to the handsome market square, and the Vanner Gallery is in prime position for any of them with eyes not glued to their phones.

I feel privileged to have been invited to show in the gallery’s first exhibition, curated by Prudence Maltby, who I’ve collaborated with on previous projects. Her idea was to pose the question, how have connections between people, art and places, as felt by the artists, countered the isolation we’ve all experienced during Covid-19?

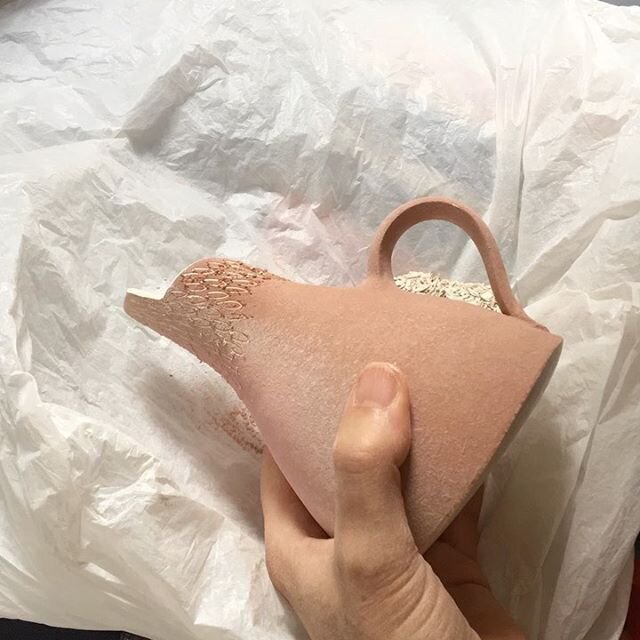

For the exhibition I’ve made two pieces which pull together ceramic influences from East and West, uniting an eastern form, the moon jar from 16th C Korea, with a western decorative tradition. My twin preoccupations with more self-expressive surface treatment - borrowed from English West Country slipware and heightened during Covid - and the more anonymous, let-the-materials-speak aspect of glazed stoneware, descended from the centuries-old tradition of oriental ceramics, both seek the attention of the viewer.

As I’ve previously written, daily walks in the spring of 2020 were a necessary solace. To be able to lose myself in the emerging profusion of leaves and buds was for me, as for many, a distraction that fed into a renewed appreciation of how beautiful and varied the natural patterns that surround us are, if we take the trouble to look.

I’ve used sgraffito as a direct way of drawing on pots since I was at school, when I first learned about and emulated harvest jugs from Devon and Cornwall. These 17C earthenware pots were made to mark special occasions, always with a sense of bounty, and often covered in profuse decoration borrowed from leaf and flower forms. Returning to this theme was what pulled me back into making after the initial paralysis of lockdown; a far more expressive version of the more restrained surface treatments that had characterised my output before the pandemic.

Apart from referring to form as a shorthand for a particular shape, I should also underscore the importance of good form as one of the fundamentals of good pots. Really this is a universal quality of any pot that originally was made to fulfil a function, from African cooking pots to Vietnamese rice bowls. ‘Form follows function’ used to be the college mantra for domestic ware, and the form of a good pot owes its principles to engineering and architecture in the same way as a sound bridge or tower is made with an understanding of materials and gravity. The unadorned form of the moon jar exposes the swelling volume of its interior, and the way the narrow foot and wider lip makes the pot appear to be ready to float away, like the full moon in a dark sky. Decoration has to earn its keep on such a form, and can neither be an afterthought nor camouflage.

Inevitably there is a tension where influences come from different cultures, not just aesthetically but in what values are embodied in the work. Ceramic practice has always absorbed and reflected the influence of cultural meetings. This was particularly evident in the Oribe ware of 16th C Japan, when Portuguese traders first had access to the previously locked-down country and western motifs began to appear in the Japanese arts of the time. Since college days I’ve been fascinated by the cheek-by-jowl proximity of fluent pattern-making and luscious, pooled glazes on the same pot. It was a reaction to the austerity of the ceramic practice which held sway up to that point, and expressed an energy and joy that for me is irresistible.

In 20th century and contemporary ceramics the tension between apparently ‘spiritual’ eastern and more ‘self-conscious’, design-led western practice has at times been the subject of intense debate. It began when Bernard Leach came to England and introduced the Oriental aesthetic to pre- and inter-war England and reached a crescendo in the 70’s and 80’s. A moon jar which Leach purchased in the East, and brought to England with him, he subsequently gave to Lucie Rie, whose seminal work owes nothing to the oriental tradition. This seems to me to be a point of focus in the dialogue about the twin threads of why we make pots - to belong to an anonymous tradition of a noble culture, or as an act of individual expression? These are not mutually exclusive motivations, but it’s a rare potter now that doesn’t sign their work. In today’s brand-dominated market it is practically a necessity, and I have lost sales due to an unclear maker’s mark on my work. My guess is that there is no maker’s mark on that ancient moon jar, which paradoxically perhaps now occupies a prized place in the Korean gallery of the British Museum. This classic Korean form, originally made for storage, is thus elevated in western ceramics to its iconic status.

Today, the noise of debate has quietened and the sources of inspiration of makers’ work are often taken for granted or unremarked, or lost in the plethora of unattributed images crowding the internet. Still, the influences and embodied values remain evident and distinct, and sometimes defended, in the work of makers aware of even the main threads of the histories of world ceramics.

In my jars I am attempting to synthesise influences that are equally important to me; and perhaps in doing so, asking a more overt question on where we stand today on the blending of cultural ideas. Is borrowing other traditions appropriation, or to be celebrated as a continuing, creative and appreciative response to the inevitable cultural mingling of our interconnected age?