Why thorough preparation is good for the material and the maker.

Many years ago I learned a little about Chinese brush painting. Before even picking up a brush, the first task was to grind the solid ink stick with water on the ink stone to achieve the deepest possible black, opaque and syrupy, to be progressively diluted for all the lighter tones when painting. Watching the ink gradually thicken as I circled the stick a hundred times clockwise and another hundred anticlockwise was quite hypnotic.

The meditative action of grinding the stick on the stone was helpful, our teacher said, not just to prepare the materials properly, but to ready our muscles and minds for the painting ahead. It was important to ease away tension and encourage an alert, but relaxed state of mind and body that would be reflected in unforced, confident brushstrokes.

I think about this often when I wedge clay ready for throwing. Today the sense of heightened awareness could be called mindfulness. Noticing the gradually improving texture with each cut of the wire is calming. It doesn’t feel like a chore, but a rewarding process of conditioning the material, improving its plasticity and tuning in to its consistency while limbering up my arms. It gives me time to focus on the pots I’m about to make and anticipate the flow of clay through my fingers.

I also think about Paul Barron, the tutor at Farnham who taught us the efficient rhythm of wedging back in my student days. I’d seen pictures of Mick Casson wedging in the book of the 70’s TV series, The Craft of the Potter, but it was Paul I learned it from: Cut in half; lift; drop; rock; turn over; rock again; give the clay a quarter turn and drop the far end on the batt; repeat. His showpiece was to ask a student to push a small coin into a whole bag of clay (20 kg then, making our 10 or 12 kg bags today look puny). He would, he said, find it within 10 cuts of the wire. As far as I know, he always did, but it was really the fluent, energy-efficient way he placed and handled the heavy mass of clay in a series of concise moves that was impressive.

He used his whole body, with the mass of clay extending towards him over the front edge of the bench. When he cut through it the front half would drop onto his knee, which he’d use to help bounce the clay back up, reducing the effort needed to lift it above his head. It would slam back down onto the half on the batt, expelling air and spreading the clay back out to near its original proportions.

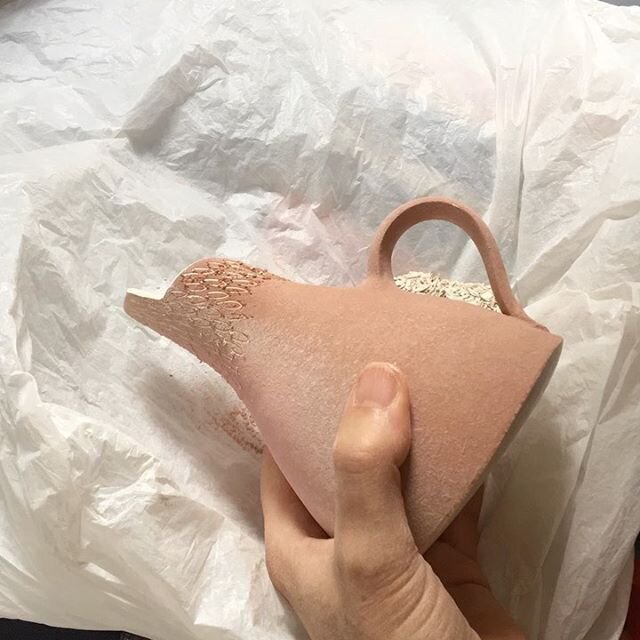

As he wedged the clay he explained the process, and how it interleaves the irregular soft and firmer parts so quickly and thoroughly. The original mass, after the first cut and drop, becomes two layers, and the number of layers continues to double with each cut of the wire, to four, eight and so on. Ten cuts produces over 1,000 layers in the clay; 20 over a million. During each sequence the clay is rocked back down to its original thickness, compressing the interspersed layers so that they are completely amalgamated. The clay’s consistency can be fine-tuned this way, by adding a piece of firmer clay if it seems too slack, or smearing on some throwing slops if it feels too stiff. The differences are quickly worked in, and over time the conscious judgment of whether the clay is ready becomes an instinct. The pocks and ripples disappear and the smooth, cellulite-free surface seems almost elastic.

Paul also described how individual clay particles are flat, and that the plasticity of clay is credited to the ability of these platelets to slide over each other’s surface film of water. The compression of wedging forces the particles into parallel layers, like coins finding their most efficient arrangement, improving their readiness to move, sliding over each other. Wedged clay has a grain, a definite advantage for slab building, adding strength in the flat plane. Accurate wedging also ensures that the clay surfaces are always convex, so that the impact of the top half thrown down onto the bottom half can’t trap, and instead expels air.

Follow the link or cut & paste into a new window to see the video: https://vimeo.com/285708633

For throwing small pots I weigh the wedged clay and then knead each piece in my hands quickly to establish a concentric pattern to the particles, so the clay has a head start on the wheel, the platelets ready to slide over each other as they move around and upward. For bigger pieces I spiral knead on the batt, another distinct and efficient way of mixing clay that is less uneven in texture, and of stiffening overly soft clay.

Throwing is a practice that demands more of clay than any other, apart perhaps from pulling handles. Good preparation not only makes the job easier, it sometimes makes it possible. Throwing with poorly prepped raw material is a miserable experience, especially when learning. While a pugmill will mix anything thrown into it, it does nothing for plasticity, or for the sense of understanding intimately the nature of the clay that is gained through handling it directly.

These preparatory processes and the time and skill they take is invisible in the final pots, but have contributed enormously to my own pleasure in making. They are time-honoured methods still unbettered by any machine for priming my raw material, and me, for the task in hand.